I'll have you know that I was in the middle of writing an epic post, EPIC, about ticks and the diseases they cause when I got distracted by something shiny. Well, not actually shiny. But pink! And fluorescent! So, let's have a little chat about a tiny parasite, eh?

The Minnesota Department of Health sent out a news release recently regarding an increase in cases of cyclosporiasis (sy-klo-spore-I-a-sis) in Minnesota. Cyclosporiasis is a diarrheal infection caused by a parasite called Cyclospora (sy-klo-spore-a) cayetanensis (ky-eh-tan-en-sis). One cluster of infections has been associated with eating at a restaurant in Minneapolis. The other is associated with eating Del Monte vegetable trays containing broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, and dill dip. The Del Monte outbreak is a multistate outbreak, with 144 laboratory-confirmed cases reported so far from Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Michigan. Implicated vegetable trays have a "Best If Enjoyed By" date of June 17th. If you're anything like me, this would for sure still be in your fridge where it would remain until eaten, shriveled and limp, or covered in mold. It really just depends on how veggie-hungry I am. Don't be like me; if you have this kind of vegetable tray - THROW IT AWAY. You can read more about this outbreak, including UPC codes of recalled trays on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's website here. There is nothing right now to indicate that the two clusters are related. This happens to be the time of year that cyclosporiasis cases increase. I'll explain why later. First, let's get to know our illness-causer.

Cyclospora cayetanensis is an intestinal parasite that can cause watery diarrhea, loss of appetite, weight loss (the "diarrhea diet"), cramping, bloating, increased gas, nausea, and fatigue. Fun stuff. There are other Cyclospora species that can cause similar illness in many different animals. A parasite is a living being that cannot survive on its own; it needs something from another living being. That something can be a place to live, a particular food item, or a blood supply. The parasite typically takes without giving anything in return. Except diarrhea maybe. Not exactly a great relationship. Some parasites are big and can be seen with the naked eye, like ticks. Others are very tiny and can only be seen with the aid of a microscope. Cyclospora is one of the tiny ones. It's just a little bit bigger than a red blood cell measuring 7.5 to 10 micrometers. A micrometer is 1000 times smaller than a millimeter! For you United States customary unit people, 25.4 millimeters is equal to 1 inch. Got it? It's very, very, very small. Here's a Cyclospora selfie:

Pretty, right? This is the view from a microscope at 1000 times magnification (and zoomed in a bit using photo editing software). Okay true talk: Cyclospora doesn't just look like this on its own. We stain it. You put some poop on a clean glass slide, spread it out thinly so that you can read newsprint through it, then let it dry and stain it using a technique called modified acid fast. Pour a type of pink-red stain on the slide and let it sit, rinse with water and remove the pink stain with a kind of alcohol, then pour a type of blue stain on the slide and let it sit, rinse with water and let it dry. Cyclospora has a kind of cell wall that can take up the pink stain and resist being decolorized with the alcohol. We see in the picture above that the background is stained blue. That means the stuff in the background did not take up the pink stain and was decolorized. Instead, the background stuff took up the blue stain. Most of that blue stuff is bacteria! This is a smear of poop after all. And poop is LOADED with bacteria. Trust me. The ruler that is across our Cyclospora is used to measure things under the microscope. Each hash line is one micrometer. The oocyst (O-O-sist) here measures 9 micrometers. What is an oocyst you ask? Let us learn.

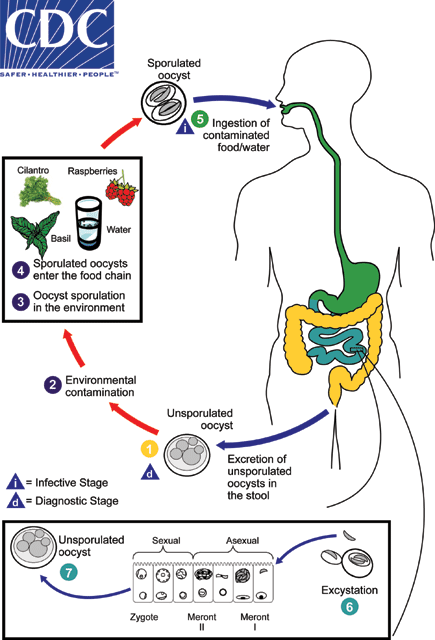

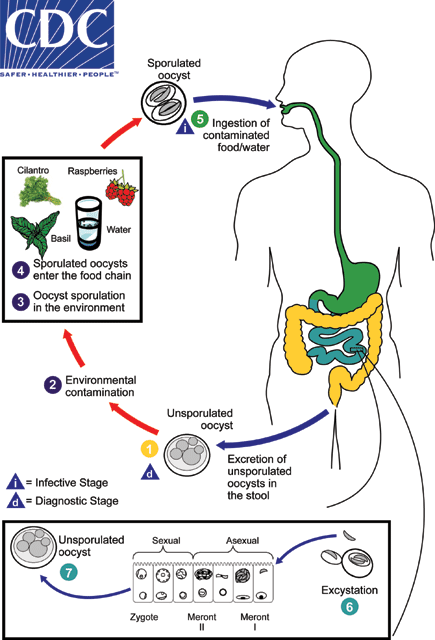

This is a representation of Cyclospora's life cycle that I shamelessly stole from CDC's website. Start at number 1 below.

We begin with an unsporulated oocyst in the environment. Think of this like an unfertilized egg. More on environment later.

Days to weeks pass at temperatures ranging between around 22 to 32 degrees Celsius, equivalent to 71.6 to 89.6 degrees Fahrenheit (come on America, get with the metric system!!).

At the optimal time and temperature for each oocyst, sporulation occurs. What happens is there a division within the oocyst from one sporont into two sporocysts. This sporulated oocyst is infective; it can make you sick if you ingest it.

How might you ingest this oocyst? When the unsporulated oocysts are deposited on food that is meant to be eaten fresh such as cilantro, basil, or berries or if the oocysts end up in the water supply, and they sporulate and become infective, then humans can swallow them and become sick.

Inside of the human gut, Cyclospora continues its life cycle. The oocyst breaks open and releases the two sporocysts which in turn release tiny wormy things called sporozoites.

The sporozoites invade the epithelial cells of the small intestine. These cells are kind of like your outer skin cells, except they are inside your body. It's this invasion of your cells that causes the symptoms I listed above. Many symptoms of infectious diseases are due to your body trying to rid itself of the offending thing. The sporozoites multiply inside your small intestine cells and mature into oocysts which are then passed in your poop.

When you get sick with Cyclospora and have watery diarrhea you are shedding the unsporulated oocysts. This is good in one way; the unsporulated oocysts are not infective. There is no direct human to human transmission of Cyclospora. There needs to be some time and the right temperature that we talked about earlier in order for Cyclospora to become infective. It's this unsporulated oocyst found in poop that we can identify in the laboratory.

Laboratories can make a smear and perform the modified acid-fast stain that I described above. This is relatively easy, and we can view the slide under a regular light microscope that most laboratories have access to. Another cool thing about Cyclospora, you know other than its pinkness, is that it's fluorescent! All by itself! If we place a drop of poop onto a glass slide and look at it under a fancy fluorescent microscope, we can look for small round objects that glow pale blue. (Note: you do have to use the right filter on the microscope in order to "excite" this wavelength of color. For you nerds out there, it's a 330-365nm ultraviolet excitation filter.)

In the middle of the picture above we see a round blue object amidst a bunch of yellow-orange junk. Again, much of that junk is bacteria. This picture really doesn't do it justice. It's really neat!

Below, we see another view of the same poop sample. How many oocysts can you find? I'll show you at the end of this post.

So far, we've learned that Cyclospora is a tiny parasite that can make us sick if we eat contaminated food or drink contaminated water. Often, the kinds of foods that can become contaminated with Cyclospora are fresh produce items like raspberries, basil, cilantro, and others. How does the food or water become contaminated in the first place? This is a question that is sometimes hard to answer and sometimes very, very easy to answer. The short story is that the food or drink somehow comes into contact with the poop of a sick person or persons. The long story can be very complicated and many times when cyclosporiasis cases are found, exactly how it happened is never fully understood. Let me tell you about a whole bunch of cyclosporiasis cases and the outcome that I can't get out of my mind.

Every year beginning around April or May, the United States sees an increase in cases of cyclosporiasis reported to health departments across the country. This increase coincides with warmer weather and the abundant availability of fresh produce that occurs in the summer months. This is not to say that produce grown within the United States is the culprit. People who get sick with cyclosporiasis have eaten food while on vacation or have eaten contaminated food that was imported for sale in the United States. When a case of cyclosporiasis is reported to a health department, the person is contacted, and health department officials ask questions about food eaten in the days and weeks leading up to the onset of illness. When there are multiple cases and similarities in food eaten are found, health department officials start to ask more specific questions. Where did you buy those raspberries? What restaurant did you go to where you ate that salad? If most of the people who are sick say that they ate salads at restaurant A, then the health department will talk to the folks at restaurant A. Where do you get your lettuce? How about garnishes, cilantro specifically? These were likely the kinds of questions being asked during the cyclosporiasis outbreaks of 2012, 2013, and 2014. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does also get involved in these investigations which are called "traceback" investigations. So-called because we're trying to trace back from the sick person to find what made them sick and where it came from so that we can fix whatever problem is happening and prevent more illnesses. Some of those outbreaks in 2012 through 2014 led officials to fresh cilantro that was imported from an area of east-central Mexico. Then it started happening again in 2015. I don't know all the details of the investigations and I certainly don't know why it took so long to reach the conclusion that was ultimately reached. You can read about it on the CDC's website and also in this FDA import alert. Pay close attention to paragraph six under "Reason for alert." FDA and Mexican regulatory authorities went to check out the farms and packing facilities that the traceback investigations led them to. They "inspected 11 farms and packing houses that produce cilantro in the state of Puebla, 5 of them linked to the US C. cayetanensis illnesses, and observed objectionable conditions at 8 of them, including all five of the firms linked through traceback to the U.S. illnesses. Conditions observed at multiple such firms in the state of Puebla included human feces and toilet paper found in growing fields and around facilities; inadequately maintained and supplied toilet and hand washing facilities (no soap, no toilet paper, no running water, no paper towels) or a complete lack of toilet and hand washing facilities; food-contact surfaces (such as plastic crates used to transport cilantro or tables where cilantro was cut and bundled) visibly dirty and not washed; and water used for purposes such as washing cilantro vulnerable to contamination from sewage/septic systems. In addition, at one such firm, water in a holding tank used to provide water to employees to wash their hands at the bathrooms was found to be positive for C. cayetanensis."

Ewwwww. 😲

There. Now you'll have that story stuck in your head too. But you know what? I still eat fresh produce and you should too! Because it's delicious and good for you and the likelihood of getting cyclosporiasis from eating fresh produce is very slim.

So, what can you do? I don't have handy list for you! Unfortunately, there's not a ton that you can do for prevention. CDC recommends following safe fruit and vegetable handing recommendations, which is all well and good. However, Cyclospora isn't easily washed off of fruits and veggies and it's resistant to many disinfectants and sanitizing methods. You can wash your produce and keep it in the refrigerator. Remember, Cyclospora needs to be at warm temperatures in order to mature into the form that can make people sick. You can make an effort to buy produce that is grown locally: frequent your local farmer's market or join a CSA. If you do happen to get sick with cyclosporiasis, don't prepare food for others, wash your hands frequently, and don't go to public pools. You are shedding many Cyclospora oocysts! Here's the picture from above where I asked how many oocysts you could find.

I counted five! Consider that this is just one view of one microscopic field in one drop of poop. The volume of poop expelled during a diarrheal event can be significant. I can't even do the math to figure out how many oocysts would be found in your toilet.

The Del Monte outbreak is growing rapidly. When I started writing this post on the 19th, there were 78 reported cases. As of today, the 21st, there are almost twice that many. Six people so far have been hospitalized. Hospitalizations are often due to critical dehydration from the watery diarrhea. If left untreated, symptoms of cyclosporiasis can last for weeks or months. Diarrhea can go away and come back. The treatment for cyclosporiasis is an antibiotic, but if you are allergic to "sulfa" drugs you can't take it. If you have a healthy immune system though, you can recover without treatment. Take care of yourself if you're sick! And throw away those veggie trays if they're still in your fridge. Be safe out there!

The Minnesota Department of Health sent out a news release recently regarding an increase in cases of cyclosporiasis (sy-klo-spore-I-a-sis) in Minnesota. Cyclosporiasis is a diarrheal infection caused by a parasite called Cyclospora (sy-klo-spore-a) cayetanensis (ky-eh-tan-en-sis). One cluster of infections has been associated with eating at a restaurant in Minneapolis. The other is associated with eating Del Monte vegetable trays containing broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, and dill dip. The Del Monte outbreak is a multistate outbreak, with 144 laboratory-confirmed cases reported so far from Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Michigan. Implicated vegetable trays have a "Best If Enjoyed By" date of June 17th. If you're anything like me, this would for sure still be in your fridge where it would remain until eaten, shriveled and limp, or covered in mold. It really just depends on how veggie-hungry I am. Don't be like me; if you have this kind of vegetable tray - THROW IT AWAY. You can read more about this outbreak, including UPC codes of recalled trays on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's website here. There is nothing right now to indicate that the two clusters are related. This happens to be the time of year that cyclosporiasis cases increase. I'll explain why later. First, let's get to know our illness-causer.

Cyclospora cayetanensis is an intestinal parasite that can cause watery diarrhea, loss of appetite, weight loss (the "diarrhea diet"), cramping, bloating, increased gas, nausea, and fatigue. Fun stuff. There are other Cyclospora species that can cause similar illness in many different animals. A parasite is a living being that cannot survive on its own; it needs something from another living being. That something can be a place to live, a particular food item, or a blood supply. The parasite typically takes without giving anything in return. Except diarrhea maybe. Not exactly a great relationship. Some parasites are big and can be seen with the naked eye, like ticks. Others are very tiny and can only be seen with the aid of a microscope. Cyclospora is one of the tiny ones. It's just a little bit bigger than a red blood cell measuring 7.5 to 10 micrometers. A micrometer is 1000 times smaller than a millimeter! For you United States customary unit people, 25.4 millimeters is equal to 1 inch. Got it? It's very, very, very small. Here's a Cyclospora selfie:

Pretty, right? This is the view from a microscope at 1000 times magnification (and zoomed in a bit using photo editing software). Okay true talk: Cyclospora doesn't just look like this on its own. We stain it. You put some poop on a clean glass slide, spread it out thinly so that you can read newsprint through it, then let it dry and stain it using a technique called modified acid fast. Pour a type of pink-red stain on the slide and let it sit, rinse with water and remove the pink stain with a kind of alcohol, then pour a type of blue stain on the slide and let it sit, rinse with water and let it dry. Cyclospora has a kind of cell wall that can take up the pink stain and resist being decolorized with the alcohol. We see in the picture above that the background is stained blue. That means the stuff in the background did not take up the pink stain and was decolorized. Instead, the background stuff took up the blue stain. Most of that blue stuff is bacteria! This is a smear of poop after all. And poop is LOADED with bacteria. Trust me. The ruler that is across our Cyclospora is used to measure things under the microscope. Each hash line is one micrometer. The oocyst (O-O-sist) here measures 9 micrometers. What is an oocyst you ask? Let us learn.

This is a representation of Cyclospora's life cycle that I shamelessly stole from CDC's website. Start at number 1 below.

We begin with an unsporulated oocyst in the environment. Think of this like an unfertilized egg. More on environment later.

Days to weeks pass at temperatures ranging between around 22 to 32 degrees Celsius, equivalent to 71.6 to 89.6 degrees Fahrenheit (come on America, get with the metric system!!).

At the optimal time and temperature for each oocyst, sporulation occurs. What happens is there a division within the oocyst from one sporont into two sporocysts. This sporulated oocyst is infective; it can make you sick if you ingest it.

How might you ingest this oocyst? When the unsporulated oocysts are deposited on food that is meant to be eaten fresh such as cilantro, basil, or berries or if the oocysts end up in the water supply, and they sporulate and become infective, then humans can swallow them and become sick.

Inside of the human gut, Cyclospora continues its life cycle. The oocyst breaks open and releases the two sporocysts which in turn release tiny wormy things called sporozoites.

|

| Picture of Cyclospora oocyst releasing a sporocyst courtesy of CDC DPDx |

The sporozoites invade the epithelial cells of the small intestine. These cells are kind of like your outer skin cells, except they are inside your body. It's this invasion of your cells that causes the symptoms I listed above. Many symptoms of infectious diseases are due to your body trying to rid itself of the offending thing. The sporozoites multiply inside your small intestine cells and mature into oocysts which are then passed in your poop.

When you get sick with Cyclospora and have watery diarrhea you are shedding the unsporulated oocysts. This is good in one way; the unsporulated oocysts are not infective. There is no direct human to human transmission of Cyclospora. There needs to be some time and the right temperature that we talked about earlier in order for Cyclospora to become infective. It's this unsporulated oocyst found in poop that we can identify in the laboratory.

Laboratories can make a smear and perform the modified acid-fast stain that I described above. This is relatively easy, and we can view the slide under a regular light microscope that most laboratories have access to. Another cool thing about Cyclospora, you know other than its pinkness, is that it's fluorescent! All by itself! If we place a drop of poop onto a glass slide and look at it under a fancy fluorescent microscope, we can look for small round objects that glow pale blue. (Note: you do have to use the right filter on the microscope in order to "excite" this wavelength of color. For you nerds out there, it's a 330-365nm ultraviolet excitation filter.)

In the middle of the picture above we see a round blue object amidst a bunch of yellow-orange junk. Again, much of that junk is bacteria. This picture really doesn't do it justice. It's really neat!

Below, we see another view of the same poop sample. How many oocysts can you find? I'll show you at the end of this post.

So far, we've learned that Cyclospora is a tiny parasite that can make us sick if we eat contaminated food or drink contaminated water. Often, the kinds of foods that can become contaminated with Cyclospora are fresh produce items like raspberries, basil, cilantro, and others. How does the food or water become contaminated in the first place? This is a question that is sometimes hard to answer and sometimes very, very easy to answer. The short story is that the food or drink somehow comes into contact with the poop of a sick person or persons. The long story can be very complicated and many times when cyclosporiasis cases are found, exactly how it happened is never fully understood. Let me tell you about a whole bunch of cyclosporiasis cases and the outcome that I can't get out of my mind.

Every year beginning around April or May, the United States sees an increase in cases of cyclosporiasis reported to health departments across the country. This increase coincides with warmer weather and the abundant availability of fresh produce that occurs in the summer months. This is not to say that produce grown within the United States is the culprit. People who get sick with cyclosporiasis have eaten food while on vacation or have eaten contaminated food that was imported for sale in the United States. When a case of cyclosporiasis is reported to a health department, the person is contacted, and health department officials ask questions about food eaten in the days and weeks leading up to the onset of illness. When there are multiple cases and similarities in food eaten are found, health department officials start to ask more specific questions. Where did you buy those raspberries? What restaurant did you go to where you ate that salad? If most of the people who are sick say that they ate salads at restaurant A, then the health department will talk to the folks at restaurant A. Where do you get your lettuce? How about garnishes, cilantro specifically? These were likely the kinds of questions being asked during the cyclosporiasis outbreaks of 2012, 2013, and 2014. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does also get involved in these investigations which are called "traceback" investigations. So-called because we're trying to trace back from the sick person to find what made them sick and where it came from so that we can fix whatever problem is happening and prevent more illnesses. Some of those outbreaks in 2012 through 2014 led officials to fresh cilantro that was imported from an area of east-central Mexico. Then it started happening again in 2015. I don't know all the details of the investigations and I certainly don't know why it took so long to reach the conclusion that was ultimately reached. You can read about it on the CDC's website and also in this FDA import alert. Pay close attention to paragraph six under "Reason for alert." FDA and Mexican regulatory authorities went to check out the farms and packing facilities that the traceback investigations led them to. They "inspected 11 farms and packing houses that produce cilantro in the state of Puebla, 5 of them linked to the US C. cayetanensis illnesses, and observed objectionable conditions at 8 of them, including all five of the firms linked through traceback to the U.S. illnesses. Conditions observed at multiple such firms in the state of Puebla included human feces and toilet paper found in growing fields and around facilities; inadequately maintained and supplied toilet and hand washing facilities (no soap, no toilet paper, no running water, no paper towels) or a complete lack of toilet and hand washing facilities; food-contact surfaces (such as plastic crates used to transport cilantro or tables where cilantro was cut and bundled) visibly dirty and not washed; and water used for purposes such as washing cilantro vulnerable to contamination from sewage/septic systems. In addition, at one such firm, water in a holding tank used to provide water to employees to wash their hands at the bathrooms was found to be positive for C. cayetanensis."

Ewwwww. 😲

There. Now you'll have that story stuck in your head too. But you know what? I still eat fresh produce and you should too! Because it's delicious and good for you and the likelihood of getting cyclosporiasis from eating fresh produce is very slim.

So, what can you do? I don't have handy list for you! Unfortunately, there's not a ton that you can do for prevention. CDC recommends following safe fruit and vegetable handing recommendations, which is all well and good. However, Cyclospora isn't easily washed off of fruits and veggies and it's resistant to many disinfectants and sanitizing methods. You can wash your produce and keep it in the refrigerator. Remember, Cyclospora needs to be at warm temperatures in order to mature into the form that can make people sick. You can make an effort to buy produce that is grown locally: frequent your local farmer's market or join a CSA. If you do happen to get sick with cyclosporiasis, don't prepare food for others, wash your hands frequently, and don't go to public pools. You are shedding many Cyclospora oocysts! Here's the picture from above where I asked how many oocysts you could find.

I counted five! Consider that this is just one view of one microscopic field in one drop of poop. The volume of poop expelled during a diarrheal event can be significant. I can't even do the math to figure out how many oocysts would be found in your toilet.

The Del Monte outbreak is growing rapidly. When I started writing this post on the 19th, there were 78 reported cases. As of today, the 21st, there are almost twice that many. Six people so far have been hospitalized. Hospitalizations are often due to critical dehydration from the watery diarrhea. If left untreated, symptoms of cyclosporiasis can last for weeks or months. Diarrhea can go away and come back. The treatment for cyclosporiasis is an antibiotic, but if you are allergic to "sulfa" drugs you can't take it. If you have a healthy immune system though, you can recover without treatment. Take care of yourself if you're sick! And throw away those veggie trays if they're still in your fridge. Be safe out there!